As of the publication of this blog, approximately 97-98% of applicants for the 2021-2022 admissions cycle have submitted their applications. There is certainly still admitting happening, with some schools pulling from their waitlists in a welcome change from last year, but it's about now that we can start looking to the upcoming 2022-2023 application cycle. It's certainly too early to make predictions with any sort of certainty, so we very much discourage making any individual personal decisions based on these very early thoughts. But given that we now have final June LSAT numbers, and registration for the August LSAT is now closed, we do have some early indicators of what we might expect to see in this third admissions cycle since the pandemic began.

A Caveat: The Big "R-Word"

Anyone who has paid attention to news coverage lately knows that there is an ongoing discussion about the possibility of the United States experiencing a significant recession in the near future. We are not economists, and we can't predict the likelihood of this happening, but we certainly hope it will not.

For the purposes of most of this blog, we're going to assume a normal, no-recession year, but at the end we'll talk a bit about how a recession could change the analysis.

Recapping 2021-2022 (and before)

To set the stage for the upcoming 2022-2023 application cycle, we want to talk about the current cycle and a bit about those before.

Applicants are down 11.3% compared to 2020-2021 but up 2% compared to 2019-2020, up 1.2% compared to 2018-2019, and up 4.7% compared to 2018-2019. (Quick note: it's difficult to accurately compare to 2019-2020 at this point, because that cycle experienced a late surge after COVID-19 delayed spring 2020 applications. Once the cycle is over, we expect this cycle to end up no more than 1% larger than 2019-2020, and it's increasingly possible—though still unlikely—that this year ends up smaller than 2019-2020.)

As for the LSAT scores of these applicants, we have seen a decline in the highest-scoring applicants compared to last year. In fact, we're down in all score bands.

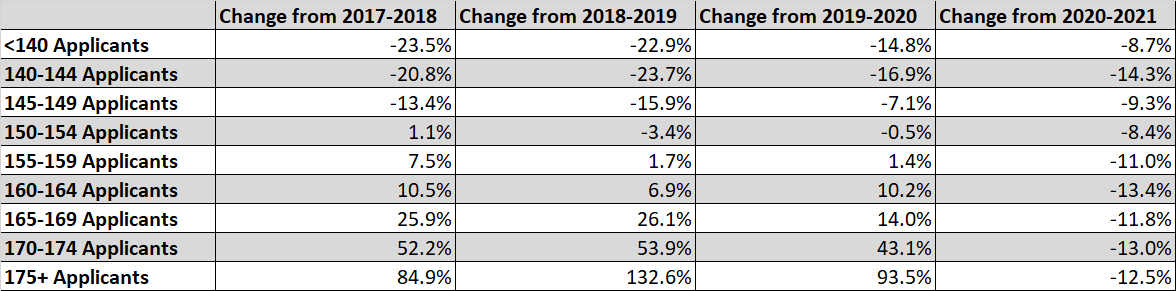

Change in Applicant Volume by Score Band as of June 30

However, when you consider that the overall volume of applicants is down by 11.3%, the declines in the highest-scoring LSAT bands aren't particularly notable, and they are less significant than we expected based on last year's inflated LSAT scores at the top. The highest-scoring LSAT bands still make up a larger share of the applicant pool compared to the cycles before 2020-2021.

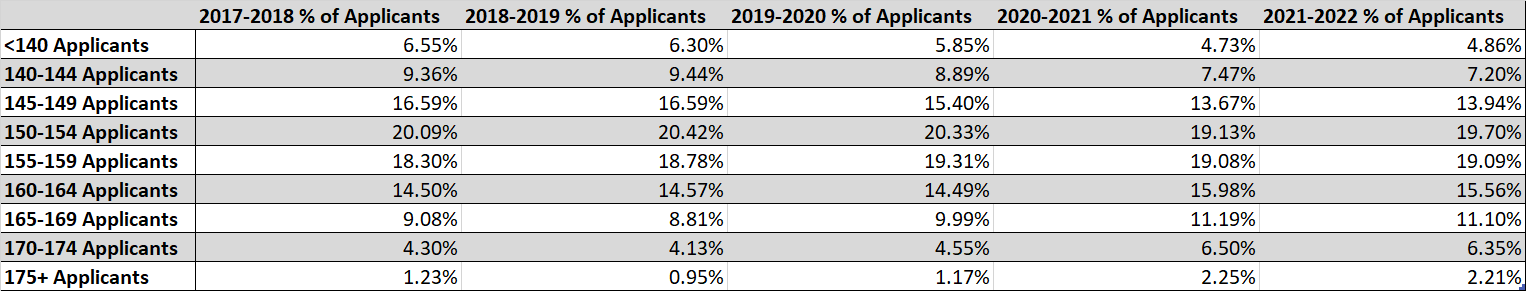

Score Band Share of Applicant Pool as of June 30

Applicants in the 165+ score ranges make up 19.66% of applicants to date this year, which is virtually indistinguishable from last year, when they made up 19.93%. That is a much larger share than 2019-2020, when they made up 15.72% of applicants, or 2018-2019 when they made up 13.89% of applicants. This 165+ share of the pool has gone up by quite a bit.

Meanwhile, the share of low-scoring applicants has declined. Applicants with LSAT scores lower than 150 make up 25.99% of the applicant pool to date, basically the same as last year's 25.87%, but much lower than the 30.15% they made up in 2019-2020, and even more of a decline from 2018-2019's 32.33%. The share of applicants in the middle ranges, 150-164, has been fairly consistent, growing from 52.89% in 2017-2018 to 54.35% this year.

There are a number of factors that may be contributing to this greater share of high-scoring applicants. One is that we know last year, test-takers were getting higher LSAT scores on average (the infamous "bubble," as PowerScore's Dave Killoran refers to it). We don't know whether that has been repeated in this cycle, but it could be one explanation. It could also be that there are more high-scoring reapplicants this year than usual—this appears to be the case anecdotally, and it would certainly make sense given that such applicants were more likely to have disappointing outcomes (or be shut out entirely) last year than in recent history. It could also be that high-scoring test-takers are more motivated to actually apply to law school these days than they were previously, or it could be due to the increased share of LSAT retakers we saw throughout the cycle (we know that test-takers on average tend to improve their scores at least a bit, and the highest score is what gets reported). Most likely it's a combination of all of these, and probably other factors that we may not be considering as well.

Regardless of the reasons, the composition changes in the applicant pool have had the effect of increasing competitiveness this year compared to pre-COVID cycles, despite the fact that overall applicant volume is similar. There are just more high-scoring applicants applying.

For comparison, here is what 2021-2022 applicant volume would look like if each score band made up the same share of different past cycles.

Applicants by Score Band if 2021-2022 Band Shares Matched Prior Cycles

Hopefully that illustrates how the pool, without necessarily being much bigger, is still more competitive.

The 2022-2023 Cycle

The Rollover Effect

Now for some good news. As we mentioned, we are seeing some waitlist movement this spring/summer (compared to last year—though never as much as we, and applicants, hope for). We're hearing much, much less about schools being overenrolled. There are some such cases, as there are every year, but nothing seems to even come close to the unprecedented overenrollment issues we saw after the 2020-2021 cycle. Even after glacial waitlist movement and sometimes large cash incentives for deferrals, there was still over a 9% increase in incoming 1Ls in fall 2021.

The widespread overenrollment in fall 2021 had predictable consequences for 2021-2022. Many schools that overbooked sought to bring in a smaller 1L class for 2022 to balance things, and most schools had many more deferred students than they normally would. That meant there were fewer spots available to 2021-2022 applicants, adding to this cycle's competitiveness. Thankfully, we don't expect that to happen again in the 2022-2023 cycle.

Additionally, because this cycle was at least slightly calmer than 2020-2021, and given that many 2021-2022 applicants were already reapplicants, we anticipate that there will be fewer reapplicants in 2022-2023. High rates of reapplication almost certainly contributed at least somewhat to this cycle's competitiveness and volume—reapplicants tend to apply early, and this cycle actually had more applicants than 2020-2021 up until late November 2021, despite the fact that the June-November testing period of 2021 had fewer test-takers (and even fewer first-time takers) than 2020 did. This cycle seems to have been pretty front-loaded overall—it looks like we reached the mid-point in applicant volume in very early January, possibly the very end of December. Reapplicants aren't the only explanation (maybe not even the biggest one, as applicants could also have been applying earlier trying to get a competitive edge), but we think the data, as well as anecdotal evidence, supports the idea that there were more reapplicants this cycle than usual. Applying three years in a row is an arduous task that most applicants don't opt to take on, so we don't think that we will see quite as many reapplicants next year.

Preliminary Data on Next Cycle

The LSAT remains by far the most common path to law school (more on that later), so let's start by considering LSAT registrant, test-taker, and first-time test-taker volume. About 95% of applicants submitted an LSAT score this cycle—in many ways, as goes LSAT test-taker volume, so goes the application cycle.

The 2021-2022 test cycle (which we measure slightly differently from LSAC, to try to align tests with the cycle they're used for) is now over.

Compared to 2020-2021, there was a 12% decline in test-takers overall. Even more interestingly, there was a 19% decline in first-time test-takers—this application cycle saw record shares of retakers. 49.3% of LSATs administered from June 2021 to April 2022 were taken by people who had already taken an LSAT, meaning just 50.7% were first-time takers. That's a substantial drop from the historic numbers. Across the 2010-2018 testing years, 68% of test-takers were first-time, and only 32% retakers. In just a couple of years, we've seen that percentage drop by over 17%.

This decrease in first-time takers helps explain why the number of applicants to law school isn't higher than it is despite far more LSATs being administered than in years past. More LSATs aren't necessarily translating into more people who have a score to apply with—after all, a person can only be one single applicant, even if they've taken the LSAT three times.

We've been seeing this trend of increasing retaker shares for a while now, and it is certainly possible that that trend will stop or even reverse (we saw evidence of this with the June 2022 LSAT, which was comprised of only 32.5% retakers—though what will happen to that figure by the time the 2022-2023 cycle is over remains to be seen). If the proportion of retakers drops overall, then there could be more potential law school applicants even on smaller test-taker volume. For now, the decline in first-time test-takers during 2021-2022 is another bit of evidence that we might see less rollover in the coming cycle.

We're also particularly interested in the significant decline in total LSAT volume from January to April of this year. Total test-takers were down by 27% in that period, and first-time takers were down by 36% compared to 2020-2021. It's hard to compare to test years before that—that period in 2019-2020 was a mess due to COVID-19-induced test cancellations and chaos, and in 2018-2019 there were fewer LSAT administrations in that timeframe (compared to this cycle's four). Still, it's something to compare to—from January to April 2019, there were about 1,600 fewer test-takers than this year in the same period. First-time data isn't available, but we'd guess that if it were, it would likely show fewer first-time takers this year.

The question now is what 2022-2023 test volume will look like. The data we have now is very preliminary—only one of the cycle's tests has been administered so far—but here is what we do know.

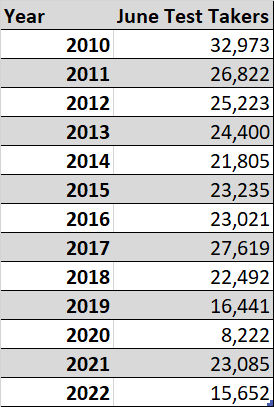

There were 17,740 registrants for the June 2022 LSAT, and 15,652 individuals actually took the test. The June 2022 administration was smaller than any June LSAT since 2010, except for the June 2020 LSAT (which was in the midst of the initial COVID outbreak and LSAC's pivot to online testing).

June 2022 did have a noticeable increase in the percentage of first-time takers, as we noted earlier, going from 59.1% last year to 67.5% this year. However, total first-time takers were still down by 22.5%.

One significant caveat to comparing this year's June numbers to prior cycles' is that there are far more LSAT administrations per year now than in years past. LSAC has doubled the number of tests per year from the historic four, a change that we applaud. Predictably, this has reduced the number of test-takers per administration, and it may account for some of the increased share of retakers as well. So June 2022 was down, yes, but what if there was simply a shift in volume to later tests? Or what if a previous test cannibalized some of the expected June volume? Let's look at those possibilities.

The April 2022 LSAT was not a large administration—8,482 people sat for the April test, and 45% had already taken it at least once before—so it seems unlikely that April took much from June, and it doesn't explain why June was down compared to the June 2021 administration since there was also an April 2021 test.

What about upcoming tests? Maybe June volume shifted somewhat to later administrations. The next LSAT to be administered is in August, and registration for that test closed yesterday with 23,593 people signed up. By comparison, in August 2021 there were 24,908 test-takers, and in August 2020 there were 25,471 test-takers (there were no other previous August tests). From sign-ups alone we know there will be fewer August test-takers than either of those years, but the final number will be noticeably smaller than the peak registration number we're seeing now. There is always "melt" between the initial registration count and test day count—for example, June 2022 initially had 24,833 registered, but by test day there were 17,740, a drop of nearly 29%; April 2022 initially had 13,732 registered but 8,712 by test day, an almost 37% drop; March 2022 saw a nearly 36% drop; etc. It's possible that this attrition rate will decrease this cycle, as LSAC has realigned their score release dates and registration deadlines such that test-takers from the previous administration will typically be able to see their scores before the window to sign up for the next LSAT closes (a change from past years that we very much commend). There's good reason to think August will be on the "less rather than more" end of the "melt" scale, but the number will drop to some extent, as it always does. Conservatively, we'll probably see at least 6,000 fewer August test-takers this year compared to last.

As for tests after that, it's just too early to tell. There are still several weeks left to register for the September 2022 LSAT, which wasn't an available date the last two years, and that could certainly be eating into August numbers (perhaps significantly). September and later test dates could very well make up some or all of the volume we aren't seeing in June and August. We also don't know what first-time ratios are going to be for those tests, which could make up some of the difference from prior years. But with every test that has lower volume, there is more and more ground for later tests to make up.

The LSAT Score "Bubble"

We don't know for sure whether 2021-2022 LSAT scores have declined compared to 2020-2021's abnormally high results—while we have access to LSAT score data for the applicant pool, that doesn't tell us how many of those scores might have been obtained in prior LSAT cycles, and it doesn't tell us anything about anyone who didn't apply (keep in mind that higher scorers are more likely to submit applications on average). Very early cycle data suggested those first tests of the year did see a decline in average score, though depending on distribution, that might or might not translate into actual good news for applicants. If that has continued, and remans true this cycle, it would help bring applicant competitiveness down to more normal levels. We could even see a scenario where there are about the same number of overall applicants, but a less top-heavy distribution yields a less competitive cycle for applicants.

Other Factors

By now we suspect most people have heard that the ABA is considering eliminating the requirement that applicants to law school submit a standardized test score. It's not certain that this will actually happen—there are a number of procedural steps before any final decision. Right now we would put our money on this initiative going through (the national mood is much more favorable than it was when the ABA last considered this, though there are still many vocal detractors), but it is very possible that it does not. Even if the ABA does eliminate the standardized testing requirement, however, it's not likely to have much impact this cycle. The ABA House of Delegates won't be considering the proposal until February 2023, and at that point they could allow the change to be immediate or choose to delay it. Even if it was immediate, a decision in February is unlikely to lead to a sudden surge in applicants during the same cycle.

Another consideration is that a recession might not even be necessary to impact the application cycle. Nonstop media coverage of a possible recession might have the effect of pushing some prospective applicants who are on the fence to apply this year.

Student loan reform/forgiveness could possibly have an impact as well, if any meaningful headway is made in that arena. If people suddenly have less debt from prior education, it's certainly plausible they may be more willing to pursue law school. However, realistically, the student loan forgiveness numbers that we are seeing experts speculate on do not seem large enough to make a measurable difference in the cycle.

Something else to consider is admissions officer planning. They are as aware of talk of a possible recession as everyone else. They're also aware that recessions bring more applicants. We'd hope that means they'll move slowly this year. No one wants a repeat of 2020-2021, and the easiest way for a given school to prevent that is to be slow and careful in its admissions decisions. We realize that isn't exactly what applicants want to hear, but ultimately, regardless of the timeline, law schools have to enroll a class for the fall. The decisions will come; we just think they might be a bit slower than normal (not unlike this year).

But What If a Recession Happens?

As we discussed earlier, the possibility of a recession is a caveat to the analysis above and the expectations we have as a result. Significant recessions have historically led to increases in the applicant pool, and if young college graduates' (or soon-to-be graduates') experience of the economy takes a substantial downturn in the near future, that could certainly lead to a wave of applicants that we wouldn't be able to predict based on the data we have now.

The timing of a possible recession would matter quite a bit. If there is a surge of applicants starting in late winter or spring 2023, it likely won't have too much impact on those who applied before then (except with waitlist movement)—by mid-February, typically about two-thirds of applicants have submitted, and that's also when the earliest application deadlines start rolling in. If the timeline is later than that, we likely would not see any significant effects on law school admissions until the 2023-2024 cycle. Of course, the ideal outcome is no recession at all, but even if there is one coming, depending on the timeline it may not necessarily significantly impact the competitiveness of the 2022-2023 cycle. It remains to be seen.

Conclusion

As we mentioned at the beginning of this post, no one should be making any plans based on how they think 2022-2023 might go—if you're considering reapplying, strategy-wise we recommend assuming that next cycle will not yield stronger results for you individually in lieu of a higher LSAT score or other significant differences in your application.

For now, though, the upcoming cycle is looking less competitive than both of the previous ones. How much so remains to be seen. Right now, our very early guess for next cycle volume is that it will be down 3-6%, but we'll have a much better idea and an updated projection after the August and September LSATs, and there's still the obvious giant asterisk in regards to the economy. Overall, we're happy that there are at least some encouraging signs for applicants after a brutal two years, but we still have the whole cycle yet ahead of us. As more data comes in, we'll continue to update our analysis.

.png)