*Note: We are now open for new J.D. admissions clients for 2025-26 and 2026-27!

X

In this episode of Status Check with Spivey, Ann Perry, the University of Chicago Law School's Associate Dean for Admissions and Financial Aid, joins Mike Spivey and Anna Hicks-Jaco to tier-rank law school admissions strategies sourced from the folks over on the r/LawSchoolAdmissions subreddit. They talk about a huge range of topics, including personal statements, letters of recommendation, resumes, work experience, retaking the LSAT, attending law school forums, the value of using a consultant, and more.

You can listen and subscribe to Status Check with Spivey on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and YouTube.

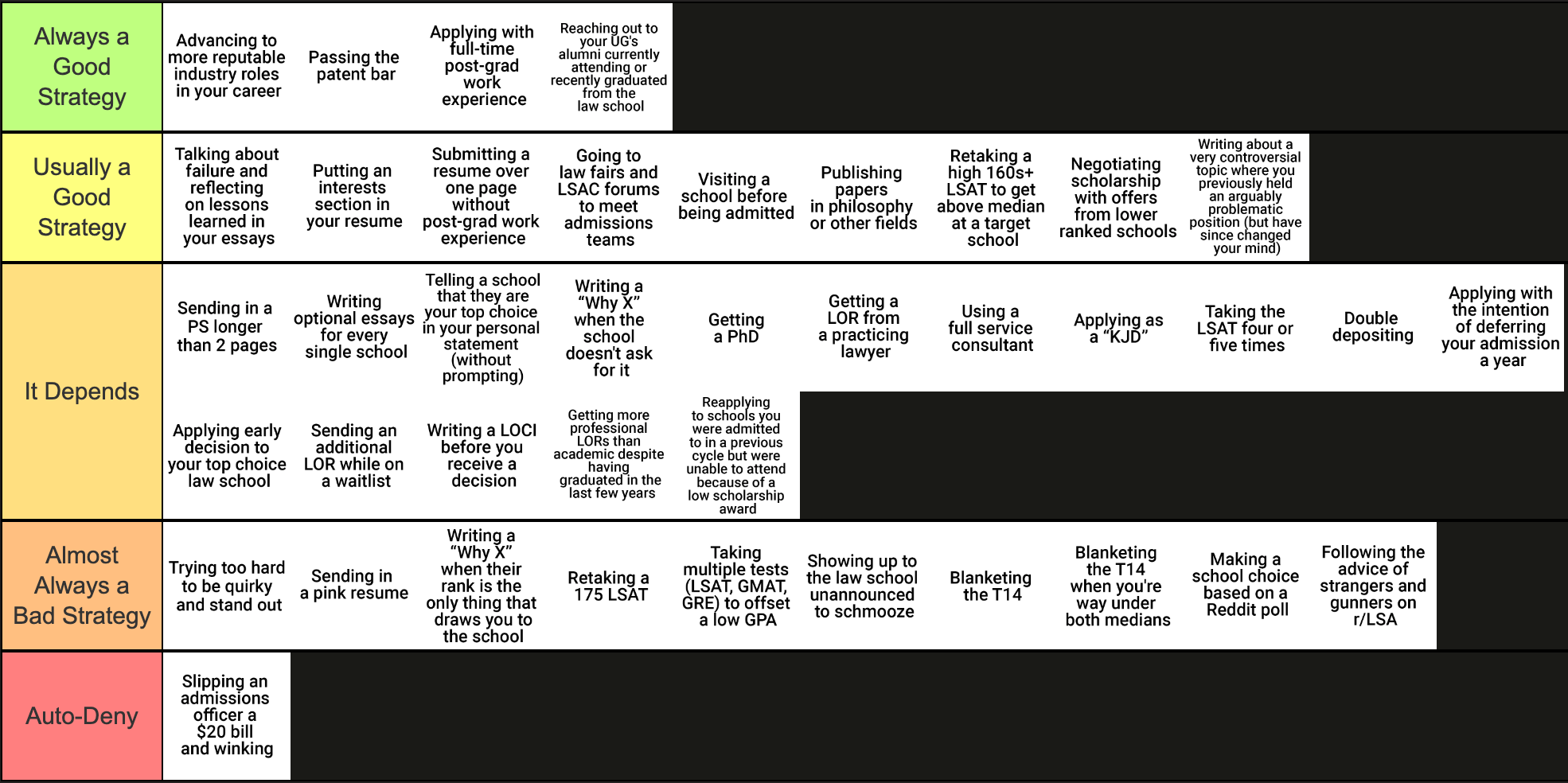

Here are the final tier ranks (please note that several of these were on the border and/or elicited mild disagreement—be sure to listen to the episode or read the transcript below for important notes and context):

Anna: Welcome to Status Check with Spivey, where we talk about life, law school, law school admissions, a little bit of everything. I'm Anna Hicks-Jaco, Spivey Consulting's president, and today I'll be talking law school admissions with two individuals who collectively have over 50 years of experience working in law school admissions offices and making decisions on files.

Mike Spivey, the original and sometimes host of this podcast, is Spivey Consulting's founder and CEO and a former admissions officer at Vanderbilt and WashU law schools. We’ll also be joined by Ann Perry, the current Associate Dean for Admissions and Financial Aid at the University of Chicago Law School, where she's led the admissions office for the past 22 years, before which she earned her JD, practiced as an attorney, and also worked in admissions at the University of Illinois Law.

We're doing something a little bit different today. We're going to play a tier ranking game, essentially, where we'll rank different admission strategies as “always a good strategy,” “usually a good strategy,” “it depends,” “almost always a bad strategy,” or “auto-deny.” We got the list of strategies from the folks over on the r/LawSchoolAdmissions subreddit, and we got a ton of responses, so while we couldn't go through every single one of them, we did rate the vast majority, and thank you to everyone who submitted strategies. If you'd like to follow along visually, we'll put the full tier list in our blog post for this episode. You can find a link to that in the description. Without further delay, let's tier-rank some law school admission strategies.

Okay, so let's just dive right in! The first strategy that we got from Reddit was sending in a personal statement that's longer than two pages. Ann, what do you think? Always, usually a good strategy, it depends, almost always a bad strategy, or auto deny? I have a feeling we're not going to have many of those.

Ann: It really depends on what the school's instructions are.

Anna: Yeah. Mike, I'm seeing you nod.

Mike: I mean, this is a layup. If the school says no more than two pages, it's always a bad idea to go over two pages. But some schools don't say that, and then it would be, “it depends.”

Anna: Depends on the content, depends on whether you are adding to your personal statement if you're going over those two pages. As with all things, read every school’s instructions very carefully, and follow their instructions.

Okay, “trying too hard to be quirky and stand out” is the next one. And the example given was a personal statement along the lines of, “You're probably thinking this is just like any regular essay,” type of essay. Thoughts, Ann?

Ann: Almost always a bad strategy.

Anna: Yeah. Mike?

Mike: If the question had been “trying to stand out,” I would like it. You want to be your authentic, genuine self. So it's the “too hard” that I think has—well, I can't speak for Ann. If you're trying too hard, you're not being authentic and genuine. If you stand out naturally, and most people do, most people have a differentiated story in them, and it's natural, it's your story—then I like it.

Anna: Agreed. Concur. We're going in “almost always a bad strategy” given the wording of trying too hard to be quirky and stand out.

Okay—talking about a failure and reflecting on lessons learned in your essays. Mike, I suspect you might want to talk about this one.

Mike: Yeah, I like this one. I would say, usually a good strategy. Let me give context, and I'm curious what Ann thinks about this, but I would say that the vast majority of essays, even at the graduate school, law school level, are still, “The day I won the county fair, they paraded me around the market square.” So there's still a little bit braggadocio. And because the majority are talking about strengths, by definition, you're differentiating if you talk about a failure or what you learned, and then how you sort of went on with life, putting a pin in that failure and trying not to replicate it. So usually, to me, that would be a good strategy. Now, if every person listening to this podcast wrote about their failures, then it wouldn't be differentiating. I’m curious what Ann thinks.

Ann: When they're writing about this, not just talking about the lessons they’ve learned, but also talking about the growth and the maturity they gained from this, the resilience from this experience, it’s also something that I really like reading about in these types of personal statements.

Anna: Agreed. Okay, I think we are all on the same page so far, so doing well!

Next up, we have writing optional essays for every single school. Thoughts, Ann?

Ann: Depends—because it depends on how the essay comes across. It has to be pretty authentic and not just rewriting the school's website.

Anna: Thoughts, Mike?

Mike: Yeah, I would say if the school asked for seven, you probably really want to try to do one or two to show interest in the school. Even if they ask for two, you probably want to do one, but to Ann's point, if you're just regenerating words that you don't believe in, that you're reading off their screen, if you don't believe in the words you're writing, never do the optional essay.

Anna: Yeah, I think in general, if it's worth it for you to apply to a school, it's worth it to do your best and to try to write the optional essays if they apply to you. But certainly if they just don't apply to you, if none of the topics are things that you can write about authentically, then don't write that essay. So we're putting this in “it depends.”

Mike: Let me give an anecdote, Anna, that I know you're aware of. We have people who come to our firm because the previous cycle, they didn't do well. And a number of times, what we see when we reverse engineer their previous applications is, they didn't answer any optional essays. So that's worth noting.

Anna: Yeah.

Ann: I just would like to add, these optional essays are just another opportunity to get in front of those admissions committees. So use them to get information to them.

Anna: Okay. Sending in a pink resume is our next one. Thoughts, Ann?

Ann: Almost always a bad strategy, if not auto-deny.

Anna: Mike?

Mike: I am not a fan of absolutes. So maybe there's a scenario where you have a 1.0 and a 145 and you're applying to Chicago and you say, “What the heck, I'm going to do everything I can.” So I'm blurred between auto-deny and almost always bad.

Ann: Can we put it halfway, Anna, can we?

Anna: So unfortunately there is no function for halfway. I think we can probably stick it in “almost always a bad strategy,” because I don't think it's strictly an auto-deny. You know, if someone has a wonderful application in every other respect, this would certainly show poor judgment, but on its own, is it enough for an auto-deny? Final calls?

Ann: Probably not.

Anna: Probably not.

Mike: If you're marginal, yes; if you're really strong in every other aspect, probably not.

Anna: Okay, we'll stick it in “almost always a bad strategy” and hope that people are listening to the podcast to know that it is truly on the border of auto-deny.

Next up, putting an interest section in your resume. Mike?

Mike: I am a huge fan. The macro data, the meta-analysis is that in hiring—and the hiring process is very similar to the admissions process—the number one reason why people are hired is when they're relatable to the person doing the interviewing. That overrides the skill of the applicant vis a vis the need for that skill in the job. So relatability is the number one factor why people get hired.

I think it's—Ann can correct me if I'm wrong—there's a certain degree of, if you're reading an applicant and they're from your hometown or have something relatable, your subconscious mind likes them more. So to begin with, that's a benefit. Number two, it differentiates them. If they have a cool differentiating—high-altitude trail running—how could it possibly hurt?

Ann: I agree. But which one do you put it? Always a good or usually a good?

Mike: I hate absolutes, so I'm going to say “usually a good,” but the only reason it would be a bad idea is if it takes a one-page or a two-page resume and flips it to a two-page or a three-page resume, and the interests are banal and ubiquitous.

Ann: But I do like these parts of the resume, because I do think, as Mike said, you get to know more about this applicant, more personal stuff that is interesting and unique. I think it's a nice little touch. But I would include a “usually a good strategy” because I've seen some of them go awry.

Anna: Yeah, okay, I think that makes sense. If I were doing this podcast and doing this exercise alone, I probably would have put it in “always a good strategy,” not because people don't do it wrong, they do, but because if I am looking at my application, I think that you should try to put them in there and you should format your resume such that it does not bring you two pages if you are one page, or three pages, and you should simply choose interesting interests! But I suppose if you truly just don't have any interesting interests, you certainly shouldn't lie. I'm okay with putting it in “usually a good strategy,” the two of you agree.

Okay, “telling a school that they are your top choice in your personal statement without prompting.” I don't think any personal statement prompts quite ask for your interest in a specific school, but schools are changing their prompts a lot lately, so I won't state that as an absolute, speaking of not speaking in absolutes. Ann, what are your thoughts? I suspect you see this sometimes.

Ann: I definitely see it. I think it depends, because it depends on how it comes across. It works when it's authentic. It works when I really believe the applicant means it and it comes across that they're being sincere and authentic about it, and I don't feel that they're writing that to every school.

Anna: I think we've all probably seen sentences at the end that look like templates where it's like, oh, you just dropped in every school's name right here.

Ann: Yeah, so I don't like it to be the last sentence in the personal statement. I like it to be worked in somewhere if it's going to be used. So…

Anna: Organically, yeah.

Ann: Because I'm not new to this. I do know people are applying to more than one law school.

Anna: Mike, thoughts?

Mike: I would just add that, downstream, if you say “you're my number one school” and it turns out that's not true, it could hurt them in the merit scholarship aid. If the school's like, “Oh my God, they told us we're their number one, and now they're trying to negotiate scholarships by leveraging other schools,” it's going to hurt you there. So if it's genuine, say it. If it's not a hundred percent true, I wouldn't say it. So it depends.

Anna: Okay. Writing a “Why X” essay when the school doesn't ask for it. Thoughts?

Mike: This is so school-specific, because it depends so much. What I would say is, if you want a heuristic, if the school doesn't ask for it, save it for a letter of continued interest. On the flip side, we do know some schools that don't ask for it that like it.

Anna: Ann, what are your thoughts?

Ann: I agree completely with Mike. It depends. I think if you really feel the admissions committee needs to know it now, then add it. We have optional essays that, as addendums, you can include it. I think they're also helpful in letters of continuing interest if you're on the waitlist. So it really depends, but they can be helpful.

Anna: Alright, sticking that in “it depends.” Mike, I like your heuristic. Typically if they don't ask for it, better for a letter of continued interest. But there might be a situation where you have really differentiated reasons for wanting to go to this particular school and it does make sense to communicate that.

Okay, so, “submitting a resume over one page without post-grad work experience.” Ann, I'm curious your thoughts on this one.

Ann: I like it. I would say “it depends” to almost “usually a good strategy,” but I don't want to encourage people to make stuff up. The resume is something that really helps guide the admissions committee on what you've been doing and gives a good outline to all the applicant’s experience, academic experience, extracurricular experiences, summer experiences. And I encourage anyone to put in the experiences you've had during your summers. I worked at Lou Malnati's Pizza for eight years, every summer during college. I had other experiences, but I made sure to put that in. Because the customer service is important, and I don't want students to feel like they don't put in their summer jobs as a life guarding at a pool, day camp, because it's not working at a law firm or doing something legal. Your resume goes over two pages because you include all that, that is A-okay with me. But don't make it go over two pages by having an inch of white space between each activity.

Anna: Don't force it, just to get to two pages, certainly. But if you have the content for two pages, it sounds like “absolutely.” Mike, thoughts?

Mike: Yeah, I mean there's a lot of myths out there. This falls in the myth category. If you're in your twenties and your parents say you need a one-page resume, yeah, in the 1960s you needed a one-page resume. Society has changed a lot. We’re just in a different world where people are doing a lot more things; there's a lot more opportunities to do a lot more things. How do we say it when we're working with people? “Give us the kitchen sink”—we need to know what you've done, and then we'll edit out if it’s just superfluous or ridiculous. But unless the school says, “We want your resume to be one page,” I would err on giving more rather than less. Usually a good strategy.

Anna: Okay, so we're falling in “usually,” it sounds like—Ann, you are sort of on the border of “usually” and “it depends” and Mike, you’re on “usually,” so are we good with putting it in the “usually a good strategy” category? With the caveat that you should not be forcing it if you don't have the content for two pages.

Mike: Yeah.

Ann: Yeah, I don't know how you differentiate the caveat though.

Anna: People are listening to our podcast to hear all of our context [I hope!]. I will say, anecdotally, Mike and I worked with someone this past cycle who had a full two pages when she was applying straight out of undergrad, and that was because she worked full time, she had leadership experiences in five different organizations, she had summer internships every single summer. She did so much that we would have had to cut substantive items to get her to one page, and that wasn't what made sense. And she got into tons of wonderful schools; she's going to Harvard next fall.

Getting a PhD. Thoughts, Ann?

Ann: It depends. I think a PhD is a time commitment, a financial commitment. I think if you're getting a PhD and then going to law school or getting a PhD while you're applying to law school, there needs to be some reasons for that. At Chicago, we actually have questions in our application directed towards people with a PhD or applying to PhD programs to kind of suss that out. We have additional essays, just because it's such a niche group of people that we want to get more specific information.

Anna: Mike, thoughts?

Mike: Yeah, I'm sort of on the bubble of “it depends” and “a bad idea.” If we're looking at this through the lens of, “I'm doing this for law school admissions,” don’t go get a PhD thinking it's going to dramatically increase your admissions chances. It differentiates, but that's a good chunk of your life you're wasting just to differentiate at the smaller remove. Spend more time studying for the LSAT. Keeping in mind PhD programs are not about teaching, they're about research. So if you have an incredibly passionate area of research, and you want that to intersect with a JD, yeah, that makes sense, but that's a really small population sample. It depends.

Anna: Yeah, this is an interesting one because I think it would be a different equation if we changed the word “getting” to “having.” If someone already has a PhD, is that going to be a positive in your law school application? Yeah, probably. But if you're thinking, should I get a PhD as a law school admissions strategy? That probably doesn't make sense in a vacuum, as Mike was saying. As Ann was saying, if there are other reasons, then certainly. But getting a PhD as a law school admissions strategy, I think we're good with putting in, “it depends.”

Ann, I'm seeing you make some pondering faces. Would you disagree with my notion that it's probably a positive in your favor if you just have a PhD already?

Ann: It is a positive, but I want to know why you're now coming to law school with that PhD, what your goals are, what are you going to do with that law degree? Is it legal academia? Are you going to go to practice? What are you bringing? So that's why we added these extra questions to get a better sense on the JD PhD people.

Mike: And the thing I was going to add, and I'm curious if Ann agrees. There are people who are professional students who get six, seven degrees, and that really doesn't really bode well for you as an applicant if you're just getting degree after degree.

Ann: I think there's value to these degrees, like these master's programs that we're seeing coming through. Just because it's always good to learn, right? Learning is good, but I want to hear the story. I want the application that tells a story, and how is that adding to the law degree? I don't like to see people going to get these master's programs or getting the PhD just because they think it's going to make their law school application better.

Anna: You need to have an explanation. You need to have a coherent application that explains to admissions officers why you're doing what you're doing. Okay, so that one landed in “it depends.”

Moving on to our next strategy—advancing to more reputable industry roles in your career. Thoughts, Ann?

Ann: I might even go to the absolute “always a good strategy,” because it’s showing growth, it’s showing progression, it’s showing you’re doing well. You’re growing in your role and you’re going to be successful. And that is showing—I think it will bode well for your future as a lawyer. So I think I'm going to go “always a good strategy.”

Anna: I like it. This would be our first “always a good strategy,” but I don't know, Mike, your

thoughts?

Mike: I mean again, I hate absolutes, and let me just bring this up. Almost every day I speak with lawyers, and every week I speak with doctors. Those are the two groups of people I speak with the most. They hardly ever use absolutes. Lawyers hardly ever use absolutes. What I would say is, of course getting promoted, advancing, is positive, of course. The only reason I'm even hesitant is there’s a time value to money. So if you're being promoted from waiter to head waiter to assistant manager to manager, and you're putting off law school, at some point, you want to go to law school, just don't go up the Chili’s food chain up to Regional VP, just for a promotion if you want to go to law school. I still would probably put this in “always a good strategy.” What is a promotion if not—other signing off on your talent?

Anna: Okay, we'll land this in “always a good strategy” with that caveat that, if you're putting off law school for years to try to advance in your role, that very well might not be a good idea. The other thing that I will quickly flag is that, if advancing to more reputable industry roles in your career would make it such that you will not be able to study for the LSAT at all and you think you're just going to have to go take it cold, some sort of extreme situation that I don't think applies to the vast majority of people, then maybe you should think about that. But I agree. In terms of just in a vacuum, getting promoted, doing better in your job, absolutely. That’s going to be positive. That’s going to be in your corner.

Okay. Going to law fairs and LSAC forums to meet admissions teams. Ann?

Ann: I think this is “usually a good strategy,” because you're just gathering more information. I don’t think this is going to get you into that law school just because you showed up, I think it’s helpful for you personally as an applicant just to be gathering information. But don’t think it’s going to save you time down the road on your application. And I don’t think you should guarantee that the admissions officer that you're speaking to is actually going to be making the decisions or is going to remember you down the road, because we meet hundreds and thousands of people throughout an admission cycle. I just think as an applicant, it personally just helps you along.

I want to remind students that there’s still a lot of virtual stuff going on that you might not even have to go to a fair or a forum. You can still go online, check out our website coming up in August when we have it all updated. We have virtual stuff going on all the time.

Anna: That's a great point for sure. If you’re not able to get to a law fair or an LSAC forum in person, there are probably options online for a lot of the schools that you're interested in applying to. Mike, thoughts on this one?

Mike: Yeah. I'll be pretty frank and candid. It’s usually a good strategy unless you’re an obnoxious person. The problem being, if you’re an obnoxious person, you’re the least likely to recognize that you’re an obnoxious person. I had obnoxious people, and Anna has, too, meet me at forums and I flag them as negative. Now that’s rare, but I remember the person who came up to me who said, “Harvard, Stanford, Chicago, maybe Vanderbilt as a safety.” So what did I do? I flagged that person. We didn’t admit them. Their judgment was horrible. But usually, I'm a huge fan of gathering information, and in the rare cases, you make such a good connection, the dean of admission says, “Hey, here’s my email address, stay in touch.” That happens. So it’s usually a good idea.

Anna: All right, we’re on the same page for that one.

Next up, visiting a school before being admitted. This is somewhat similar, but there is a different angle to it, a different nuance. Mike, what are your thoughts on this one?

Mike: Try to introspect. If you have the resources, I think it’s a wonderful thing to do. And, you get a good feel for fit, which U.S. News & World Report has no metric for. And fit is very important. If you're going to blast into the admissions office without calling them, without emailing them, and storm in there like a storm trooper, announcing how great you are to the world, then it wouldn't be a good idea. So I would say, “usually a good strategy.”

Anna: Ann, thoughts?

Ann: I agree with Mike, usually a good strategy if you can afford it. It’s not necessary. I think it comes down to costs. It gets expensive visiting schools. I think you should save that money for the schools you’re admitted to. I think visits, and maybe you both can correct me if I'm wrong, is much more of an undergrad thing prior to admission. I just see it going on, on our campus, tons of undergrads come and visit campus. But it’s also looking at the schools’ websites to see what they do for prospective students. We do have visit days for prospective students. But it’s not a necessity by any means.

Anna: Okay, I think we might have our very first “auto-deny” with this one. Slipping an admissions officer a $20 bill and winking. Thoughts, Mike?

Mike: Auto-deny.

Ann: Auto-deny.

Anna: I think that's an easy one.

Next up, getting a letter of recommendation from a practicing lawyer. Ann, what are your thoughts on this one?

Ann: “It depends,” I’m going to say, because it depends if this practicing lawyer truly knows you and can write a good letter of recommendation about you and about you as your potential as a lawyer and about your potential as a law student.

Anna: Yeah. Mike?

Mike: I have nothing more to add. It depends. You always want to ask people who know you versus how mighty do their titles sound.

Anna: Don't go out and find your neighbor or your uncle’s friend who’s a lawyer and have one conversation with them and then ask them to write a letter of recommendation just because they’re a lawyer. But certainly, if you work closely with a lawyer, they know you well, they think highly of your aptitude for the practice of law, good idea. Landing that one in “it depends.”

Next up, we have one that I think Mike, you'll certainly want to speak to. Using a full-service consultant. What are your thoughts on this one?

Mike: I mean, it depends. Like, a lot of people don't need to. It bothers me that there’s consultants out there that say, “You need to use us,” because a lot of people don't. We turn away a ton of people. But I also think that—and Ann can probably speak to this component—there's a lot of bad applications out there. So if you're concerned and you don't have a mentor, or someone with a good feel for this stuff, I see nothing wrong with speaking to a consultant on a free call and seeing if they can offer a perspective you don’t have. And if they can, it might be helpful. I was surprised when I was in admissions, how many applications were just genuinely poor, which is kind of the genesis of this firm. On the flip side, if you're just crushing it across the board, numbers-wise, you have a good feel for yourself, you have a mentor who went to law school, you probably don't need a consultant.

Anna: I will add that most people who are applying to law school have some limit on their resources. So if you are looking at, should I spend my money taking this LSAT prep course or should I spend it on a consultant? We're going to tell you pretty much 10 out of 10 times that if it's that choice for you and it’s binary, spend your money on LSAT prep. That's going to be more bang for your buck generally.

Generally, there are lots of poor applications, and having a consultant will prevent you from hitting those landmines and from submitting just a poor application. But you can also prevent that by doing your research online, listening to podcasts like this one, reading books about it, looking at articles, talking to admissions officers, talking to admissions deans if you have meetings. There are other ways that you can get the information. It might not be as tailored to your specific situation, but plenty of people are able to put together a stellar application without a consultant. So I would agree with Mike, “it depends.” Ann, anything to add on this one?

Ann: I completely agree, it depends.

Mike: Anna, let me add two more things. One is, if you have a high level of anxiety, keeping in mind how much we dedicate training to helping in these areas, it might be helpful. And two is, just given the trend towards more and more interviewing, if you need interview help, there's probably plenty of consultants out there, including us, that can just help you with that kind of stuff.

Anna: Okay. Applying as a “KJD,” so someone who's going straight from kindergarten on through their JD without any breaks, no work experience, no gap year before college, just straight on through. Thoughts, Ann?

Ann: I'm going to say it depends. I think if there's a good reason for now and you are ready to go now, at Chicago, we have a good group of people that come straight through and do well. You know, you need to prove to the admissions committee in your application that you're ready to continue, that you have the maturity, that you're ready to take on three more years of education and are professional and have good experiences outside of education. Like your summer experiences have showed some maturity, but it depends.

Anna: Mike, thoughts?

Mike: Definitely depends. I think people should do what they're gung-ho about doing. If you're gung-ho about doing—if they are gung-ho about going to law school, there are plenty of people who are KJD. I think the one thing that people never talk about, you cannot predict the next cycle. The next cycle might be twice as competitive as the current cycle. Yeah, we have data that shows that getting work experience gives you a little bit of a bump. We have proprietary data, I believe right, Anna?

Anna: Yep.

Mike: On the flip side, that bump might not offset the fact that the following cycle, there might be a huge shift in the bell curve to LSAT scores being +2, +3, like during LSAT-Fex. Which is why I think you just should follow what your heart wants to do.

Anna: Yeah, macro-level, as Mike said, there is data that shows that if you have meaningful work experience, you probably are going to do better, within the same application cycle, all else being equal—which in the real world, it's not all else equal. But there is all this surrounding context, there’s so much nuance and there’s so much that's different at the individual level. So that sort of statement of macro-level data should not mean something definitive for any given individual. So we're putting this one in “it depends,” I think that makes a lot of sense.

Next up, we have one that's more specific, so, “passing the patent bar.” Ann, what are your thoughts on this one?

Ann: This is such a niche topic, and it's for those people that want to probably be patent lawyers, that I'm going to think it's always a good strategy to pass the patent bar. So it's one of my few absolutes for this exercise.

Anna: Love it. Mike?

Mike: I agree a hundred percent. Why else would you be taking the patent bar? As a former dean of career services, those people always got jobs. It's always a good strategy unless you're listening to this podcast and you are mishearing us and you go randomly take the patent bar and don't want to be a patent lawyer, right?

Anna: Okay, we're putting this in “always a good strategy” for the people who it would apply to realistically.

Okay, so this is the flip side of applying as a KJD. Applying with full time post-grad work experience. Thoughts, Mike?

Mike: If you already have it, always a good idea. I mean, unless you got fired, or worse, got fired for theft or fraud. If you don’t have it, we're back to that, what we already talked about as far as KJD.

Anna: Yeah. Ann, I saw you nodding.

Ann: Yeah, I agree, completely.

Anna: All right, we're putting this in “always a good strategy.”

Okay. Publishing papers in philosophy or other fields. This was at first posed to us on Reddit as two separate sort of, publishing papers in philosophy versus publishing papers in other fields. If the two of you have distinctions there, please bring them up. I folded them into one. Ann, what are your thoughts on this, publishing papers, doing academic research?

Ann: I think it's usually a good strategy, but I’m cautious a little because I don't want people to be doing things just because they think it's going to make their law school application successful. Do it because they have the love of the academic research. Because it takes a lot to get a paper published. That's why I hedge it to the “usually a good strategy.”

Anna: Yeah, okay, that makes sense to me.

Mike: A hundred percent what Ann said.

Anna: Perfect, “usually a good strategy.”

Next up, we have reaching out to your undergraduate's alumni who are currently attending or recently graduated from the law school that you’re applying to. Thoughts on this one, Ann?

Ann: I think it's always a good strategy to gather as much information as you can about the schools you're interested in. And reaching out to your undergrad alumni is a great option to do that, and usually your undergrad pre-law advisor might have that information for you. So there's ways to get that information and they're usually very helpful to talk to people. So.

Anna: Yeah. I would agree. It's not going to hurt you unless, if you're such a nightmare person that they feel the need to report you to the admissions office.

Ann: Exactly.

Anna: I can't imagine.

Ann: Yeah.

Anna: Mike?

Mike: As long as you don't do it abrasively, it’s a good idea. I would keep in mind that there was a period in my life—it’s toned down a lot—where I was getting 350 emails a day. People are abusive with email. If the person doesn't respond, it's not about you, it just means they're busy.

Ann: Exactly!

Mike: Don't keep emailing them.

Anna: Yeah. You might not get a response, it might be the case that nothing comes of it, but

it's probably not going to hurt you.

Ann: Very good point.

Anna: Okay, next up we have, writing a “Why X” essay when the school's rank is the only thing that draws you to them. Ann, what are your thoughts on this one?

Ann: It depends on how this essay comes across. If it’s truly coming down to ranking and that’s how it reads, then it’s not going to really work well for I think admissions committees. But, anything that you're writing in your application needs to be authentic, and I wouldn't focus on rankings at all.

Anna: Yeah, probably not a good idea to even mention it. One thing that I will add is that if you’re applying to a school, and especially if they ask for a “Why X” essay, doing the research to write an essay that doesn't just say, “I'm interested in you because of your ranking,” which is a terrible idea, for the most part if you’re applying to the school, you will come across things that draw you to that school, that make you interested in that school, that align with your interests, align with your goals.

So I think, even if you are just applying to a school because they were within a certain range of rankings that you decided you wanted to apply to, doing the research for that “Why X” essay you might find out that it's not just the ranking that draws you to that school.

Ann: Exactly!

Anna: Mike, thoughts?

Mike: I would say for the vast majority of schools, it’s actually a bad idea. Ann’s in a different hemisphere. I mean, I was at two top 20 schools, but even then, we didn't particularly like it if they talked about rankings, because there were still 15 schools, 16 schools ranked above us. So, I would say for the vast majority of schools, it's probably a bad idea. I'm in the “almost always a bad idea” category.

Anna: Okay, we can stick it there since this is going to be published on our website. But people should listen to the podcast and know that there’s some extra context around that.

Retaking a high 160s or higher LSAT score to get above median at a target school. We’re getting into a few questions about testing now. Mike, what are your thoughts on this one?

Mike: I took a quick look at the questions. I didn’t see every one, but I know another one’s coming that I don't like. This one I do like. Look, schools see all your LSAT scores, but they’re not pulling out a calculator and averaging them. I hate this idea that no, apply in September with a lower score because schools love a September application. Schools love highly qualified candidates a lot more than they love September 1st applications. So I'm in “usually a good strategy”—if you're below median LSAT and you want to get up to or above the median, usually a good idea.

Anna: Ann?

Ann: I think if you feel you're going to be able to do better on the test taking it one more time, then do it. But if you're taking it for the fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh time, that's where I start getting a little questionable about it. There's a lot more to an application than the test that we're looking at.

Anna: Okay, we'll put this one into “usually a good strategy,” especially if you are retaking it for the first time, but this kind of gets us into our next one, which I just moved up our list, which is taking the LSAT four or five times. Ann, what are your thoughts on this one?

Ann: I'm going to start with “it depends,” but I might be able to talk myself into another category. I think you need to take the LSAT when you’re ready, when you’re prepared and not something that you’re just going to keep taking to try to do better, because I just see that's not usually what happens on these multiple test taking. I do see jumps sometimes. I do see people do better, but sometimes I see people do worse. Sometimes I see people do way worse. And then I start thinking, when it's four or five times, I’m like, what are they doing this? It seems like a lot of wasted Saturdays taking a test, preparing for a test. I really like seeing someone taking the test once, doing the best they can, and making the rest of their application as strong as possible.

I get it, the test is a part of the application that you have some of the most control over at that point when you're applying, so doing the best you can is something that they focus on. So taking it once, twice, a third time… like I said, when I start seeing four or five, six, seven—10 times I’ve seen—I start getting a little jumpy about the application. What else is going on in this application, is what I start thinking. This is between “it depends” and “almost always a bad strategy.”

Anna: Mike, what are your thoughts on this one?

Mike: I'm on that bubble too. I think three is pretty okay. You start getting up to four and it's almost always a bad strategy. And you get above four… I'll give you one example when it was a good strategy. You’ll probably remember this, Anna, but Karen and I were doing this. We had a client in Asia whose wife lived in New York City. And he really wanted to be in New York City at NYU or Columbia. So he took it seven times, and on the seventh time did very well and got admitted to both NYU and Columbia. I mean, he had a really good reason to take it seven times.

Anna: Yeah, yeah.

Ann: And I should also give this caveat, if someone's taken it five or six times over, like, a five-year period, maybe that justifies it a few more times than two or three.

Anna: I think if you're taking the LSAT four or five times, you should certainly write an addendum to explain the circumstances. And I will say just anecdotally from my experience, which is certainly more limited than either of yours, but when I saw 4 or 5+ LSATs, it was much more frequent to see those scores coming in right around the same score, or the exact same score, or even going slightly down, than seeing a huge jump at the fifth or sixth test. Be honest with yourself about, what can you actually change? What will you be able to do better if you do take that test a fourth or fifth time?

This is a toughie, are we landing at “almost always a bad strategy,” or “it depends”?

Mike: In between for me.

Ann: I’m really in between, but I know we can't land it there.

Anna: I think “it depends” is broad enough. Especially with the context of this podcast.

Ann: I’d almost go “bad strategy,” but I'll go “it depends.” I am convinced.

Anna: Okay. More on the LSAT. Retaking a 175 LSAT. Ann, thoughts on this?

Ann: I was going to say it depends, but after our conversation, there could be a circumstance that it depends on what happened on that test date. But I'd need to see an addendum that said that testing date, when you took it and got that 175, something happened at the test center and that you did retake it and you did better. This is a tough one for me because I just would be jumping up and down with a 175 and be applying and moving forward.

Anna: It does strike me as probably a pretty rare circumstance that someone has a really bad experience taking the LSAT, the marching band was outside or whatever, and they still score a 175 and are so certain that they can score better. I imagine that's exceptionally rare. Mike, what are your thoughts on this one?

Mike: Yeah. I'm at the “almost always a bad strategy.” It's just obnoxious. You're above everyone’s medians or at everyone’s medians, so what’s the point? You're just kind of signaling a level of obnoxiousness. I’m not on the radar of LSAT board that much, but I see this posted from time to time on there when I peek over there. I just don’t see a really good point. Go focus on other stuff. Live your life. You have a 175. Go do other things. To Ann’s point, yeah, if something wackadoo happened where people kept interrupting the test center, Justin Kane at our firm, when he was at our firm, he had a 179, but he always was getting a 180 on his practice tests. It’s not an auto-deny, it's not that obnoxious, but to me it's almost always a bad strategy.

Ann: Yep. I'm happy to go there.

Anna: Alright, we’re putting it in “almost always a bad strategy.”

This is an interesting one that I don't think I've really ever seen anyone talking about it. One of the strategies that was submitted is taking multiple tests, LSAT, GMAT, and GRE to offset a low GPA. This is an interesting one. Ann, thoughts on this?

Ann: You have to remember not all schools take multiple tests. There’s still schools out there that just take the LSAT. So, there's so much that goes into the holistic review process and the application that I don’t think different test scores are going to offset a low GPA. “It depends” or “almost always a bad strategy.” I don't want you to just sit for the GRE because you think it's going to offset something.

Anna: One thing that I will flag is that, in terms of data and reporting, the reporting that the law school is doing to the ABA, if you have an LSAT score, that is the score that is going to be reported, even if you also have a GMAT, even if you also have a GRE. That’s just one thing I wanted to flag. Mike, what are your thoughts on this one?

Mike: Yeah. Having done this for 25 years, I’ve literally never had someone ask me that question before, so it’s really rare. I’m at the “almost always a bad strategy.” The one caveat I would say is, for sure you can take them on your own and see which one you're best at, then go with that one maybe, but submitting a GMAT and an LSAT to try to impress a law school is not going to do anything for you. So I’m at “almost always bad.”

Anna: Alright, sticking that one in “almost always a bad strategy.”

Okay—showing up to the law school unannounced to schmooze. This is an interesting phrasing of things; we could also say, you know, visiting a law school without letting them know beforehand. Just sort of coming into the admissions office to chat with people and see how that goes. Ann, what are your thoughts on this one?

Ann: I think I'm going to put this “almost always a bad strategy,” because on schools’ websites, we all have information about how to visit, how to connect with the law schools. We encourage applicants to be mindful of these opportunities and to follow directions. So showing up unannounced just doesn’t bode well.

Anna: Yeah, I think it's good professional judgment to look into what a law school says about visiting, to contact them, to let them know. If they don’t have something on their website, email them beforehand. That’s just good practice, I think. Mike, other thoughts?

Mike: Yeah. I'll tell one story that—Ann’s going to hate that I'm telling this, but it is a real story, so I'm going to tell it. I wouldn't replicate it. So Brad A, I’m not going to say his last name, showed up on our first day of orientation, and he was so chill. He was like, “Don't worry, if a couple people don't make it, and you feel like admitting me, I’m here. I’m going to sit outside.” The guy was so chill, and we had two people no show, we just admitted him. We looked at his application carefully; he was already on the margins. But don’t do that.

Ann: Please don’t.

Mike: I can think of 50 times where that didn't work for people. We had to call security once. I would say, if you did it and you were super chill and just not at the forefront, but sort of just talking to people and not annoying admissions, yeah, maybe it’ll work, but I’m still at the “almost always a bad strategy.”

Anna: I think that makes sense.

Ann: Definitely.

Anna: Okay, so, broadly: double depositing. Ann, what are your thoughts on this one?

Ann: I think, once again, it depends on the school you’re depositing at and what the rules say. For Chicago, I would say it’s always a bad strategy, because we ask that when you deposit with us, you only have one deposit out there. Now, we have no way of knowing exactly if you are depositing at other schools, so we take you for your word and you’ve signed the deposit form. So I am going to put this “almost always a bad strategy” because I can't tell, I don't know, I can't auto-deny you.

Anna: Well, I think your caveat about it depends on the school makes a lot of sense. So, for University of Chicago, almost always a bad strategy, bordering on auto-deny if there were a way to know, but other schools don’t have the same rules necessarily. So, in that case, it might be an it depends. Mike?

Mike: I get from the law school perspective, law schools do not like this. And I also think that I would add another piece of information here. By the time you have to deposit, you've had a lot of time to think this stuff through.

Anna: Sometimes.

Mike: Sometimes, right. If you’ve been admitted to four schools, and you’ve been waiting on the school for months, you really should have figured out by then where you’re going to go. On the flip side, I’m a huge fan of free will. If the school doesn’t say, “You can only deposit to us,” and you can't make up your mind, you do have free will. If you have the money to double deposit, and it’s not violating their policy, then I don’t see anything wrong with it.

Anna: We're putting double depositing in “it depends.”

Okay, so our next question is “blanketing the T14,” so applying to every single law school that is considered a top 14 law school. Mike, what are your thoughts on this one?

Mike: Yeah well, I mean, what the heck? This old dude who never went to law school, who probably can't name a single 1L law school course is telling you what the top 14 are, so then you’re arbitrarily applying to the top 14. That makes no sense to me. In any given year, that might include Georgetown or UCLA, and it might not. I would say look at the top whatever and find the ones that fit where you want to be, what you want to do. This idea of blanketing T14 is, to me—I mean, it’s not an auto-deny because we don't know you're doing it—but it’s almost always a bad strategy.

Ann: I agree. I think you need to be applying to schools that you want to go to if you get admitted and you’ve done research on. Because A, applications are expensive, applications take time to do, and we want to admit people we think want to be at our law schools. And so you're just wasting time and money and resources blanketing schools you might not have any interest in going to, moving to that city or part of the country. So be thoughtful and mindful when you're making your applications, I think. Rely on yourself when you’re making these important decisions and your research.

Anna: Yeah, I think that's really good advice. And I think this strategy is what lands you in the situation of considering whether you should write a Why X essay for a school where the only thing that appeals to you is the ranking, is by blanketing certain rankings.

We’re sticking this in “almost always a bad strategy.” The vast majority of people are not going to legitimately want to attend every single school in that range. They’re in vastly different locations. Everything from huge cities to very rural areas. There’s so much different about these schools. Do your research.

Okay, next up we have “blanketing the top 14 when you are way under both medians.” I am going to strongly guess that this is going to land in the same “almost always a bad strategy.” It's not quite an auto-deny, especially since schools don't know that you've blanketed the top 14. But my guess is it’s almost always a bad strategy. If it’s a bad strategy without being way under both medians, I don't know how this would make it better.

Mike: I put it in “always a bad strategy.” It's not even worth talking about. If you’re below both medians, why would you do that?

Anna: Anything to add, Ann?

Ann: I think once again, you need to do your research when you’re applying to schools and thinking about where you want to be and realistic about your opportunities and your choices.

Anna: Applying with the intention of deferring your admission for a year. Ann, what are your thoughts on this one?

Ann: It depends. We all understand that there's a possibility someone might defer when we admit them, because they maybe were applying for a Fulbright or Teach for America or something. But I don’t ever think it’s good to go into an application cycle knowing if you get admitted, you’re automatically going to defer. Because your application is going to be stronger after that year or two of deferring with whatever you're planning on doing that you’re going to be able to write a stronger application. So just wait and apply. Don’t feel like you have to rush and get that offer of admission and then ask for the deferment. Admissions committees are working hard in that particular cycle to get their class set for that fall. Deferments, they happen, we grant them on a case-by-case basis and we understand them, but I think there's more reason not to wait to apply when you're going to be starting in the fall.

Anna: Great points for sure. Your deferral may not be granted, and your application probably will be stronger with whatever you were planning to do in that year on your resume and having that experience under your belt. That was a really good point. Mike?

Mike: Wait for it, here comes the pun: I’m going to defer to Ann on this. She’s in the thick of these things. I used to have a strong feeling on this; I don’t even remember what it was.

Anna: All right, sticking it in “it depends.”

Applying early decision to your top choice law school. Mike, thoughts on this one?

Mike: We have a blog on this. I think there were three things I put in the blog. If it is by far your top choice for good reasons, you’re not worried about debt, and if you need an early decision boost, then it’s a good idea. So, usually a good strategy if you hit those three components.

Anna: I think the question did elaborate a little bit more about, will you be taking yourself out of the running for more scholarships? I do think the majority of people are worried and should be worried about the cost of law school. I would almost land in “it depends” based on your description just then, because for most people it does, the scholarships do matter. Ann, what are your thoughts on this one?

Ann: I agree. I think it's usually a good strategy.

Mike: If you don't need money.

Ann: If you don't need money.

Anna: I think if that's where you're both landing, I think we should put it on, “it depends.” The question doesn’t include “if you don’t need money”; I do think that that puts it in “it depends” because that's the caveat we're putting.

Negotiating scholarships with offers from lower-ranked schools. Ann, thoughts on this one?

Ann: I don't like calling it “negotiating scholarships.” We call it scholarship review. I don’t want students to think this is a negotiating. I think it’s usually a good strategy to provide the scholarship committee as much information as possible as part of our review process, the way we do things, we would want to see that information. So I’m going to put this “usually a good strategy.”

Anna: Just don’t approach it as a negotiation, especially not a hard-ball negotiation.

Ann: Right.

Anna: Mike?

Mike: Nothing to add. Usually good. Don't play Joe or Jane Business Person in the process.

Ann: Yeah.

Anna: Yep.

Making a school choice—so deciding on where you’re actually going to attend—based on a Reddit poll. Mike?

Mike: You’re asking a bunch of strangers who don’t know you to tell you where to go. Obviously it’s not an auto-deny, but it’s almost always a bad strategy.

Anna: Ann?

Ann: Completely agree.

Anna: Definitely, and almost always a bad strategy.

Okay, sending an additional letter of recommendation while on the waitlist. Ann, what are your thoughts on this one?

Ann: It depends on the timing of that additional letter. It depends on what it says. It depends on instructions from said school that you’re on the waitlist. So there's a lot of caveats to this, so I'm going to put it, “it depends.”

Anna: Mike?

Mike: I like staying in touch at a measured pace, but I would agree with Ann. You’ve got to assess why you’re sending in that extra letter of recommendation. So it depends. But I do like showing the school justifiable attention from time to time if you’re on the waitlist.

Anna: In a lot of cases, it might be a good idea, but it does depend on a number of factors.

Writing a letter of continued interest before you receive a decision. Ann, what are your thoughts on this one?

Ann: It depends on the context. I don't even know if it would make it to the file in time, to get reviewed before a decision. You know, once our files get into the review process, we take them for what they're worth right there. We don't add things. So I think it would just depend on what it’s saying.

Anna: Mike?

Mike: I remember answering this one Reddit, and the person hadn’t heard and applied in September and it was like March. You might want to just do it if you haven’t heard anything from the school. That was the one case where I thought it might be a good idea, but I’m in the “it depends” category as well.

Anna: Yeah, we interviewed Natalie Blazer, who’s UVA Law’s admissions dean, and she mentioned specifically that if you haven’t heard from a law school after three months, specifically UVA Law, that sending a quick note saying, “Hey, I’m still super interested, you’re still my top choice school,” can be a positive, can lead to an admit. That’s a very specific situation. That also—I don’t think that she was looking for a full letter of continued interest, like a one-page essay. Just wanted to add that context.

Okay, next up, we have getting more professional letters of recommendation than academic, despite having graduated in the last few years. Ann?

Ann: You definitely still need some academic, so it depends. You want to make sure these letters of recommendation are telling your story and that you’re following the schools’ instructions, right? I think making sure there's a balance. So it depends on what they’re saying and the story that they’re telling about you, if that makes sense.

Anna: Mike?

Mike: Yeah, I'm in the same boat. It depends.

Anna: Reapplying to schools you were admitted to in a previous cycle, but you were unable to attend because of a low scholarship award. Ann, I imagine that this is something that people do with the University of Chicago sometimes. What are your thoughts on this one?

Ann: I think we do see people reapplying and I think it's fine, we re-admit them. Sometimes they add an addendum, which is helpful to give a little bit of context to that decision process for us. We find helpful. I would put this in “it depends” on how they handle it.

Anna: Good advice, certainly, to write an addendum to sort of give some context and explain. Mike?

Mike: Yeah, same thing. I was just going to add, they’re going to be a little skeptical until you write that addendum, and then it probably not the worst idea. I couldn’t possibly put that in “usually a good strategy.” So “it depends.”

Anna: Let’s look at—following the advice of strangers and gunners on the law school admissions subreddit. Mike, what are your thoughts on this one?

Mike: I see a lot of bad advice online from people who say it with a lot of confidence and authority so people believe them, and that’s really nefarious and deleterious to the admissions process. So I would say that's almost always a bad strategy.

Anna: Ann?

Ann: I am right there with Mike. Always a bad strategy.

Anna: Alright, I'm kind of interested in this one. Writing about a very controversial topic where you previously held an arguably problematic position, but you've since changed your mind. And this was within the context of I think several schools’ optional essays where they ask about a time that you changed your mind. So, within that context, if you used to have a pretty problematic position, but since you've changed your mind—thoughts, Ann?

Ann: I'm going to say that it depends on how you handle the question and the reason why you're telling the story. It’s a tricky question I have to say. It’s a tricky essay prompt in a way, but I think what you want to do is try to explain how you changed and what changed. The process of changing your mind.

Mike: I’m going to say, I think it’s usually a good strategy because I love when people grow and are able to be pliable in their strong positions. But if you were a member of a hate group, and you change your mind, you might want to hire a consultant. I like that you got out of that hate group and you might have a great story, there are some scenarios where you might want to be very delicate with talking about your past.

Anna: Yeah. If you think about people like Derek Black, I think his name is, who was raised in Stormfront, in a white supremacist cult essentially, and who made a huge change during college and now speaks out on behalf of anti-racist groups and does wonderful things. I think he could write an excellent essay about this. I think, Mike, if you're landing on “usually a good strategy,” we can put it there since this is our Spivey Consulting list.

We have run out of time, it seems. But I think we have some great discussions in here. I really appreciated all of the submissions from Reddit. I greatly appreciate your time, Ann.

Ann: Great to be here.

Mike: Thank you.

Anna: Thank you for participating. Okay, thanks everyone for listening as well ,and we'll see you next time!

Ann: All right, take care.

Mike: Bye!

In this episode of Status Check with Spivey, Anna Hicks-Jaco has a conversation with two of Spivey’s newest consultants—Sam Parker, former Harvard Law Associate Director of Admissions, and Julia Truemper, former Vanderbilt Law Associate Director of Admissions—all about the law school admissions advice that admissions officers won’t give you, discussing insider secrets and debunking myths and common applicant misconceptions.

Over this hour-and-twenty-minute-long episode, three former law school admissions officers talk about the inner workings of law schools’ application review processes (31:50), the true nature of “admissions committees” (33:50), cutoff LSAT scores (23:03, 46:13), what is really meant (and what isn’t) by terms such as “holistic review” (42:50) and “rolling admissions” (32:10), tips for interviews (1:03:16), waitlist advice (1:15:28), what (not) to read into schools’ marketing emails (10:04), which instructions to follow if you get different guidance from a law school’s website vs. an admissions officer vs. on their application instructions on LSAC (14:29), things not to post on Reddit (1:12:07), and much more.

Two other episodes are mentioned in this podcast:

You can listen and subscribe to Status Check with Spivey on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and YouTube. You can read a full transcript of this episode with timestamps below.

In this episode of Status Check with Spivey, Mike has a conversation with Dayna Bowen Matthew, Dean of the George Washington University Law School, where she has led the law school since 2020. Prior to her time at GW, she was a Professor of Law at the University of Virginia School of Law, the University of Colorado Law School, and the University of Kentucky College of Law, and she has served as a Senior Advisor to the Office of Civil Rights of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). She is a graduate of Harvard University (AB), the University of Virginia School of Law (JD), and the University of Colorado (PhD).

Mike and Dean Matthew discuss the increase in law school applicants this cycle (7:42 and 18:11), advice for applying during a competitive cycle (12:16), how the large firm hiring process in law school has changed into something that "bears no resemblance" to how it worked for decades (5:11), how the public interest and government hiring process has changed as well (6:27), how AI could impact legal employment in the future (24:10), why she chose the law school where she attended (2:33), what she would do differently if she were applying today (3:36), how to assess law schools' varying "personalities" (13:22), the fungibility of a JD (16:45), advice for law students (18:53), and what it's like being a law school dean in 2025 (28:53).

You can read more about Dean Matthew here.

We discussed two additional podcast interviews in this episode:

Note: Due to an unexpected technical issue during recording, Mike's audio quality decreases from 7:35 onward. Apologies for any difficulties this may cause, and please note that we have a full transcript of the episode below.

You can listen and subscribe to Status Check with Spivey on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and YouTube. You can read a full transcript with timestamps below.

Correction: Dean Matthew's family reminded her that she actually applied to three law schools rather than two, including Harvard Law, where she received a denial.

As Emmy-winning news anchor Elizabeth Vargas stated in one of our recent episodes, "There is nobody out there who is at the top of their field, in any field, who has not been told 'no.'"

In this episode of Status Check with Spivey, Spivey consultant and former admissions dean Nikki Laubenstein discusses the financial aid and student loan considerations that prospective law students should be thinking about post-“Big Beautiful Bill,” joined by Sydney Montgomery, who is the Executive Director & Founder of Barrier Breakers, and Kristin Shea, who has led the law school financial aid office at Syracuse University for almost a decade as a part of a 20-year career in legal education.

Nikki, Sydney, and Kristen talk about the changes to student loans and student loan caps resulting from the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (9:53), the changes to repayment plans (36:08), who those changes apply to (5:31), the differences between undergraduate financial aid/scholarships and law school financial aid/scholarships (21:02), understanding tuition vs. total cost of attendance and how that relates to scholarship reconsideration and student loan caps (24:27), possible ways schools could help fill the gap especially for students targeting public interest jobs (38:31), advice for those planning to work while in law school (41:10), why prospective law students should start thinking about financial aid earlier on in the admissions process than most do (30:57), and more.

Barrier Breakers is a nonprofit that has worked with 7,000+ first-generation and other marginalized students on the college and law school application process. Sydney Montgomery, the daughter of a Jamaican immigrant mother and military parents, was the first person from her high school to go to Princeton University and then later Harvard Law School. She has dedicated her life and career to supporting first-generation students and has a particular passion for financial aid. She is a member of the Forbes Nonprofit Council and has been featured in Inc., Forbes, FastCompany, Medium, CNBC, and others.

Kristin Shea is a higher education professional with twenty years of experience, including law school enrollment management, recruitment, and financial aid; alumni, donor, and employer relations; and marketing and communications. The last decade of her career has been dedicated to financial aid, and she is passionate about helping law students make smart, thoughtful financial plans for their education. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology and psychology and an MBA from Le Moyne College.

We hope to do a follow-up episode in the spring with more information on how law schools are addressing these changes. We also encourage you to reach out to the financial aid offices of schools you're considering once admitted to learn about any programs they may offer and any assistance they can provide. As Kristin says in this episode, "The map may have some alternative directions, but you can still reach your destination, and there are many people who want to help." We have also linked a number of financial aid resources below.

Federal Student Aid:

AccessLex Institute Resources:

Free Credit Report:

Annual Credit Report.com - Home Page

Equal Justice Works – LRAP FAQ

Important Questions to Ask About Any LRAP - Equal Justice Works

You can listen and subscribe to Status Check with Spivey on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and YouTube. You can read a full transcript with timestamps below.